The wonder of waiting.

- Phil McLoughlin

- May 2, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: May 16, 2020

My father was a furnace man and I spent my last two years at school working every holiday alongside him at the iron foundry – Easter, summer and Xmas. 12-hour days spent mixing sand for the moulds; helping pour the castings; wheeling the steaming sand back to the mill to start all over again, the next morning. Sisyphus wept!

The afternoon sun often caught the steam rising from the castings, as it filtered through the holes peppered in the corrugated roof. Such moments were almost a delight - to my romantic eye. For the unblinkered, the foundry was a cross between Piranesi and Dante’s inferno. This was only the first of several, hard and dirty jobs I did in my youth. I would never want to repeat the experience, but would never wish to erase it from my CV.

I spent quite a few years at this University of Life: iron foundry labourer, railway porter, chicken factory processor, jute mill worker and road mender. Finally, I took a job as an "attendant at the asylum", as the labour exchange framed the position. Little did I know that this would transport me (eventually) to academia and (even later) a long career as a university academic and psychotherapist.

My very short time as an 'attendant' and (relatively) short career as a psychiatric nurse completed my graduation from the University of Life. Until then I had simply been getting sweaty and dirty. In psychiatry I could stay clean and gain privileged entrance to worlds above and below the daily grind. Here I was granted access to the assorted hells of ‘ordinary life’ – conveniently passed off as one form of ‘mental illness’ or another. Here, Piranesi's imagined prisons were personified; stretched on racks of their own making, or society's construction.

Later, a wise old friend reminded me that the mind is just an idea – and cannot be sick, other than in a metaphorical sense. I realised then that ‘mental illness’ is a metaphor for everything disagreeable in life – whether in ourselves or others. Ironically, society's failure to understand such 'problems in living' offered me a lengthy career in exploring how they affected people. Eventually, I realised that there could never be a 'solution' to such problems, since they were (and remain) at the core of everyday life. But, throughout this prolonged education I never had to get my hands dirty.

I was reminded of all of this recently when I re-read Brendan Behan who said: “people who say that manual labour is a good thing have never done any”. Most of colleagues from the past 40 years were 'dying of exhaustion' because they had to meet a publishing deadline or give an extra lecture. But, I made similar excuses in my own life. I needed to remind myself that I never really had to work – at least not in the sense people like my father understood it. Instead, I did ‘occasional jobs’ and then got an opportunity to do something that interested, intrigued and ultimately fulfilled me. Call it luck but never call it ‘labour’.

Of all my jobs, being a low-paid ‘attendant’ was both the hardest and the easiest. Hard, in the sense that I had no idea what I was supposed to be doing. Easy, in that I finally realised that all I had to do was sit, watch and listen. Waiting was something that came naturally to me. Hence my affection for Beckett and his long list of characters 'in waiting'.

In the 50 years since that first 'attendant' experience I wrote umpteen books about ‘just sitting and listening’ . None really captured the essence of the ‘thing’ itself. I can feel that 'attendant' memory now, but I can’t tell you – in words – what it is. If you had the time, I might be able to take you to that realisation. But we might need a lot of time and patience.

But none of this has anything to do with art. No! I am wrong - this has everything to do with art. Art is about expressing - or re-presenting - that which cannot be expressed in words - even in literature. Wittgenstein famously said “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”, prompting his friend Frank Ramsay later to say - "What we can't say we can't say, and we can't whistle it either." Wittgenstein understood that language – however sophisticated - is overrated. Although not an artist, Wittgenstein had the ‘vision thing’.

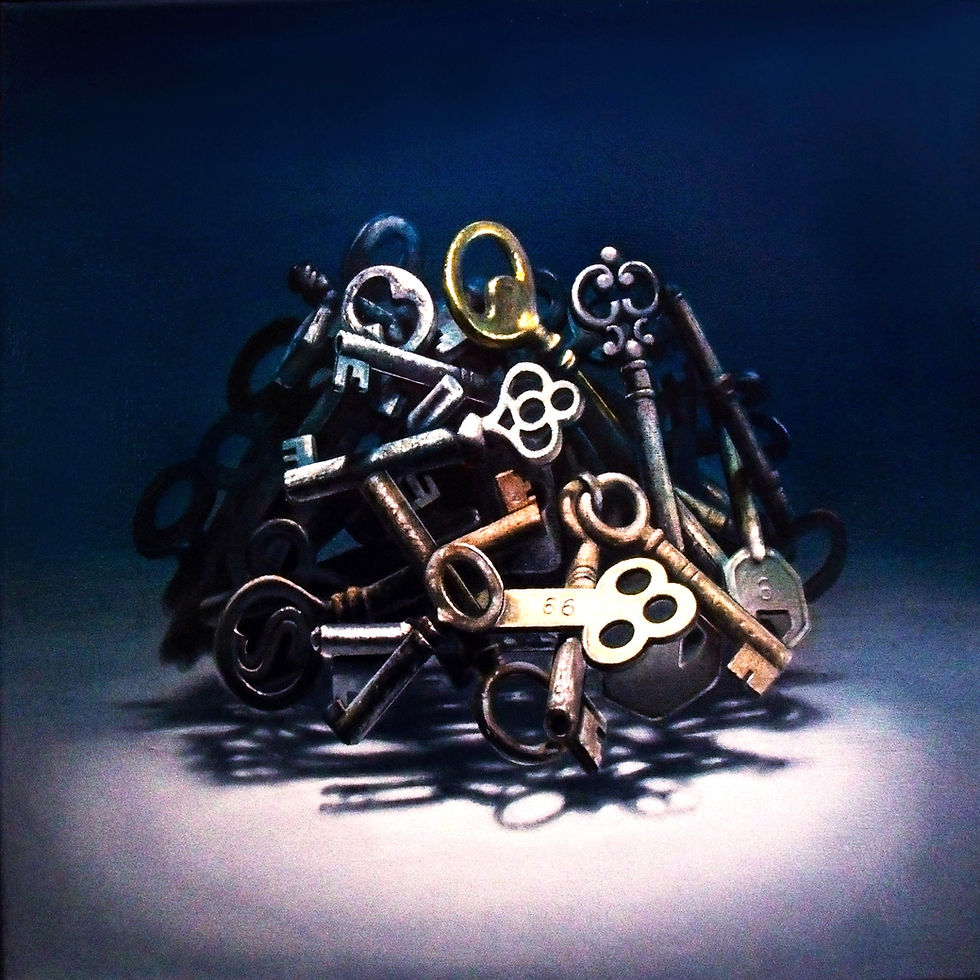

We may not be able to say it – or whistle it – but we can paint it, or shape it in clay, stone or metal; or pull together a bunch of objects; or arrange a group of people to signal ‘that of which we cannot speak’? What is interesting is the ineffable – that ‘thing’ beyond words.

What I do as an artist can sometimes be frustrating – due to my own temper and other failings. Sometimes it can appear demanding – when someone pushes forward a deadline. But I know I am the one manufacturing the frustration or demand. It can never be called ‘labour’. I chose to stand on this spot and only my curiosity holds me there.

If approached properly the ineffable will speak for itself through the work. All the artist has to do is have the patience to allow it to happen. And so I am back where I started – waiting!

Copyright - Phil McLoughlin 2020.

Comments