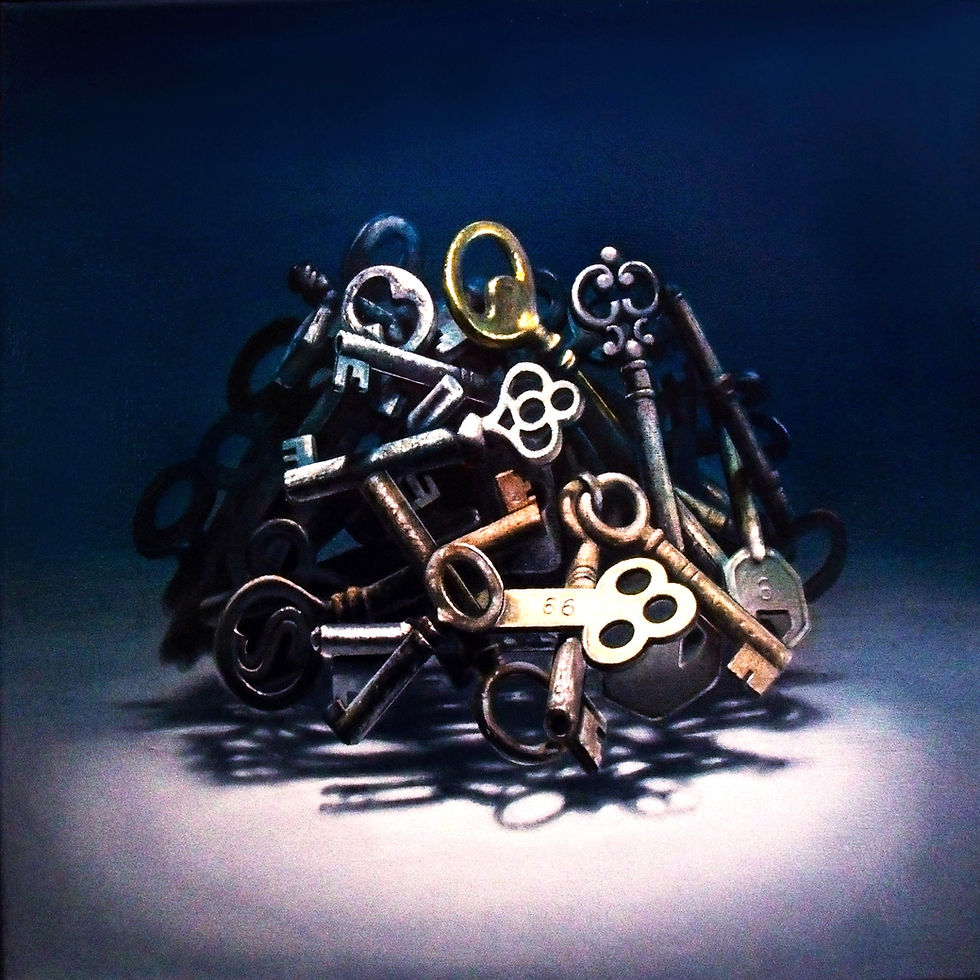

Keys to the sublime

- Phil McLoughlin

- Sep 1, 2020

- 5 min read

Over 20 years ago the psychiatrist, Howard Cutler, published "the Art of Happiness”, based on conversations with the Dalai Lama. Their book suggested, if not argued, that ‘happiness’ was was some kind of ‘right’, bestowed at birth. Something that we had ‘lost’ that could be found again by ‘earnest searching’. I wasn’t too taken by the idea at the time and, all these years later, when new ‘rights’ appear almost every day, I am even less impressed.

The sub-title of their book - ‘ a manual for living’ – was the main stumbling block. Life – and how we might live it- seems far too mercurial to be shaped and crafted by any ‘manual’. Like a multitude of others since, they were promoting the idea of life as a ‘project’: like getting fit or becoming more assertive. Their book promised the ‘solution’ to a problem which, until then, I didn’t realise might exist.

Life is a flowing thing. It surrounds every aspect of my being. I never know what is going to happen next. All I can do is try to make sense of these experiences and act in the best way I can.

Life is not a problem to be solved. As my old friend Tom Szasz once said:

“life is something to be lived, as intelligently, as competently, as well as we can, day in and day out. Life is something we must endure. There is no solution for it”.

That says it all really.

In the flow of life thoughts and feelings come and go. One moment we are happy and then – whoosh – another fickle feeling has displaced it. These reactions too will be nudged out by some other emotion or thought. Why waste time fiddling with something so transient?

Life is an experience – not a project: something we encounter – like the weather. The interesting question is: why do some encounters result in me feeling like ‘this’ rather than like ‘that’? Why do I feel ‘happy’ in both the sunshine and the pouring rain? Making sense of these ‘encounters’ is the very bedrock of my existence. When I stop making sense of such encounters I shall cease to exist.

Like most people I am often so busy doing “stuff’’ that I drift through much of my day. However, when walking our dog, Elvis, I stop, while he examines carefully a blade of grass or patch of pavement. I find myself also ‘noticing’ aspects of the world around me. Sounds, smells, fleeting shadows of the world that flow around me in space; flow past me in time. In these accidental encounters I am arrested in time. The chattering in my head ebbs away. I am lost in the moment.

Visiting art galleries offers a chance to experience an arranged version of such arresting moments. Gazing into a painting or circling a sculpture offers a short cut to an intense encounter with something beyond my small self; a world where words no longer have currency. Pure experience.

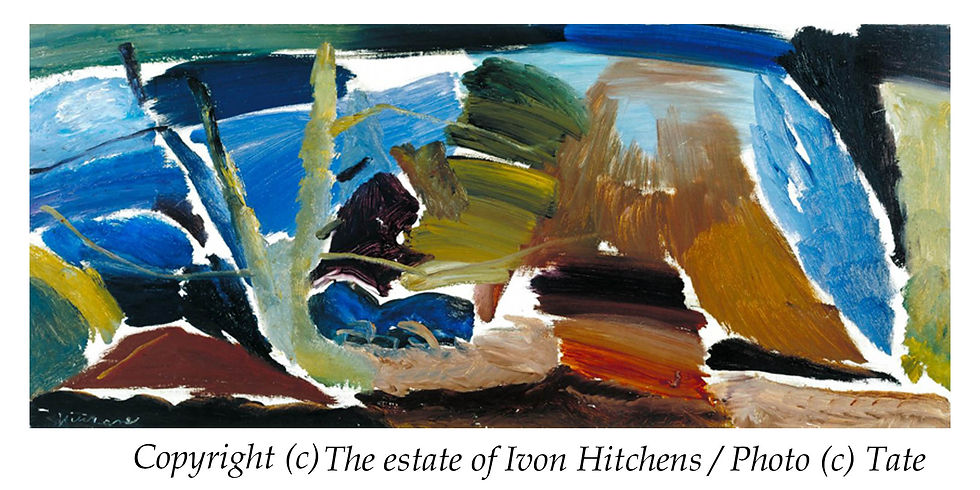

The first time I lost that sense of my small self was in Sunderland Art Gallery in the late 50s. I was about eleven years old and had wandered into a room showing works by Ivon Hitchens.

I had never heard of him so had no expectations. That day I was arrested, for the first time, by a work of art. The colours and the flowing forms in Hitchens’ paintings suggested ‘nature’ and ‘landscape’ but were like nothing I had ever seen before- in life or in a picture. I seemed to recognise these images and had the sense that they recognised me. Time stopped. I was lost in what James Joyce liked to call an ‘epiphany’. I had come to know and understand something that was far beyond my experience and wholly beyond words: the ineffable.

The real bonus was that I was alone with this experience. I went to the gallery alone and came out alone. No one ever asked me about my time there and I never talked to anyone about the visit. Indeed, the only person I told about my experience that day was my wife Poppy, more than 50 years later.

Today, that boy would, no doubt, be taking photos with his ‘phone; uploading them to one ‘platform’ or another; ‘sharing’ them with the whole world if it was interested. Aloneness no longer has much currency in the life experience.

Being alone, in the presence of some ‘thing’ that speaks, wordlessly, to us seems central to the artistic encounter. Perhaps, in such a private encounter, we also recognise some part of ourselves. This seemed to as true for our prehistoric ancestors as it does for people living today. We make ‘things’ to express something that cannot be communicated any other way. Perhaps the only point of making them is in the hope that others might encounter them; make their own sense; perhaps experience an echo of the thoughts and feelings that led up to its making. Such, otherwise useless, things might even serve as a touchstone for others to make something anew, within themselves.

A former academic colleague, Alec Grant, wrote that:

“I once stood in front of Caravaggio's The Taking of Christ, in Dublin. I lost an hour. It was a numinous experience”.

I wonder what kind of experience Alec had that day. Was he ‘filled with the presence of divinity’ - which is one reading of ‘numinosity’? Was he spiritually elevated, connected to his ‘higher emotions’ and ‘aesthetic sense’? What kind of feelings did Caravaggio’s masterpiece engender in him? Was he happy? As soon as we start to analyse, or even talk about such epiphanies, we risk turning the experience to dust.

Anyone who ‘gets lost’ in the presence of a work of art - whether painting, sculpture, music, book or play - experiences all sorts of thoughts and feeling as they engage with something beyond themselves; something ineffable; something akin to the ‘numinous experience’.As they get lost in such moments (or hours in Alec’s case) they may make a special, and lasting connection with this ‘thing’ as they sense that there is something of themselves already within the art-work.

I don’t know if art is meant to make us happy. A lot of art is unsettling or disturbing, often intentionally so - like Goya’s ‘black paintings’. If art has any function, it may be to arrest us: stop us in the tracks of our everyday meanderings; inviting, if not tricking, us into contemplation; nudging us towards Alec’s ‘numinous experience’. Art which is decorative, nostalgic, romantic or just ‘fun’, has its place. It may delight us, offer comfort, help us feel secure, but it is unlikely to change us in the longer term.

I suspect that Alec Grant walked away from Caravaggio a different man. Perhaps he knew himself in some sense ‘better’. Perhaps he was confused and genuinely lost and knew himself ‘less’. Either way, he knew that he had had a significant experience – one that might live with him for a long time. Much like my experience with Ivon Hitchens over sixty years ago.

These two, very different artists, had keys to the sublime. Through their work we get a chance to experience something we know – ‘in our bones’ – to be important, but can never fully comprehend. Awesome, in the proper sense of the word. As we become lost in their sublime handiwork we might even catch a glimpse of our true selves.

Copyright - Phil McLoughlin 2020.

Comments